According to Genesis, work was the first (and it could be argued most enduring) horror ever visited upon humanity. God cursed Adam to toil among thistles and thorns, setting in motion a legacy of labor that would define nations and generations.

Cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat of it all the days of your life. It will produce thorns and thistles for you, and you will eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.

Genesis 3: 17-19

In Greek mythology, the goddess Athena punished the weaver Arachne for her professional pride by turning her into a spider, condemning her to weave forever, and she wasn’t the only mortal to find herself facing hard labor for her hubris. Work was a common punishment in the classical world.

It seems toil and trouble go hand in hand in Western culture, and while we’ve found a cure for many of our modern ills, the spectre of labor still haunts us. Late stage capitalism’s 24/7 hustle culture remains a source of constant tension, anxiety, and even terror for humans. Authors could do worse than to toil among these thistles and thorns for the cultivation of dark tales that ensnare readers as sure as any thicket.

Write what you know, right?

By the time I was thirty, I’d been a waitress, a bartender, a dish washer, a short order cook, a baker, an administrative assistant, a teacher, a tarot card reader, and a housekeeper (to name only my most notable professional pastimes). If you’re anything like me, you should have enough traumatic workplace experiences under your belt to weave an anthology’s worth of horror. In this post, we’re going to take inspiration from Fritz Leiber’s classic weird tale Conjure Wife, which reminds us in no uncertain terms that our colleagues are out to get us (by any means necessary).

TL;DR: Conjure Wife Plot

When Norman Saylor discovers that his wife Tansy practices witchcraft to protect him and further his professional success at Hempnell College, he becomes entangled in a web of workplace paranoia and supernatural forces that threaten to unravel his life and the very fabric of the world as he understands it. As he navigates the fine line between reality and superstition, Norman realizes that his colleagues may be more than just rivals — they may be part of a clandestine cabal of academic enchantresses seeking his downfall through otherworldly means.

We all know work is horrific. How can a writer possibly make it worse?

Leiber perfectly combines an oppressive atmosphere, the complexities of care labor, and paranormal power plays to craft a workplace horror par excellence. If you, too, think work is scary as hell, file these three writing techinques under To Do.

Use the physical environment of the workplace to create a sense of dread.

From page one of Conjure Wife, Leiber begins to craft a setting that deterioriates from cozy to claustrophobic faster than you can say, “Per my last email.” Norman’s home and work lives collide in the conservative college town of Hempnell. Looking out his bedroom window he notes:

…the funny, cold little culture that the street represented, the narrow unamiable culture with its taboos against mentioning reality, its elaborate suppression of sex, its insistence on a stoical ability to withstand a monotonous routine of business or drudgery – and in the midst, performing the necessary rituals to keep dead ideas alive, like a college of witch-doctors in their stern stone tents, powerful, property-owning Hempnell.

On campus, the scene becomes even more Gothic, and Leiber crafts a setting capable of multitasking – grounding the story, creating atmosphere, planting props, and reflecting Norman’s thoughts and feelings:

From where he sat, the roof ridge of Estrey Hall neatly bisected his office window along the diagonal. There was a medium-sized cement dragon frozen in the act of clambering down it. For the tenth time this morning he reminded himself that what had happened last night had really happened. It was not so easy. And yet, when you got down to it, Tansy’s lapse into medievalism was not so very much stranger than Hempnell’s architecture, with its sprinkling of gargoyles and other fabulous monsters designed to scare off evil spirits.

If you’re looking for an alternative to the haunted house trope, a creepy old college is a great place to start. But you might also consider restaurants (The Menu), hotels (The Shining and The Sun Down Hotel), superstores (Horrorstör), and offices (American Psycho), just a few jobsites that have been used to brilliant success in workplace horror.

U.K.-based writer Richard Daniels and illustrator Melody Phelan-Clark offer several imaginative examples of workspace weirdness in their long-running zine series The Occultaria of Albion. In Volume 4, one of my favorites, they take readers on a tour of the haunted and haunting Spanton Industrial Estate (the equivalent of an American industrial park). It had never occurred to me before reading the zine that dark rides must be built somewhere. Now, I can’t stop thinking about the possibilities of that setting.

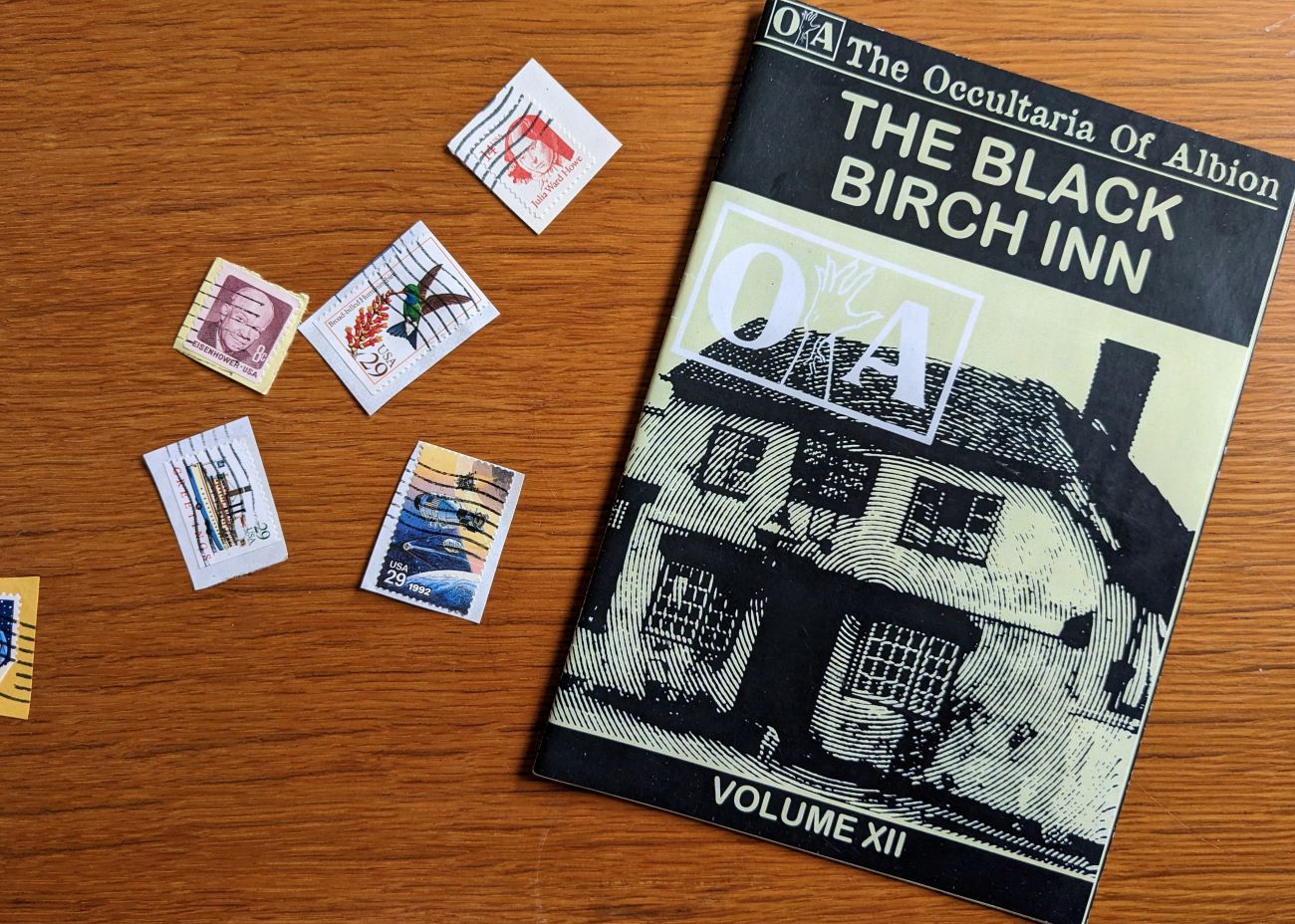

I loved Volume IV of The Occultaria of Albion so much that I recently sent it in a care package to a friend, but Volume XII is also about a weird workplace – The Black Birch Inn, where pickled toes and missing band members are just two occupational hazards.

Capitalize on the horrors of care work.

One of the things I love about Leiber’s novel is the explicit acknowledgment of the role women’s unpaid labor has traditionally played in making men’s professional successes possible. It was a progressive paradigm shift for a male writer to make in 1953. In the first chapter, Norman muses on Tansy’s part in his own achievements:

Somehow, drawing on an inward source, Tansy had found the strength to fight Hempnell on its own terms,…to take more than her share of the social burdens and thereby draw around Norman, as it were, a magic circle, within which he had been able to carry out his real work…

Tansy’s care work is manifested physically in the form of dozens of flannel-wrapped, feather-bound charms that she has hidden all around their house and on Norman’s person. “You haven’t taken a step for years without being in the range of one of my protective charms,” she tells him, before fatefully burning all of the amulets at his insistence.

When Norman destroys a final, hidden charm, he is gripped by overwhelming, irrational fear (the worst kind if you’re a rational man like Norman). Tansy, on the other hand, sleeps like a baby after being relieved of her burden. Her speedy recovery does nothing to assuage Norman’s concerns:

It wasn’t normal. He remembered her sleeping smile. Yet it wasn’t Tansy who was behaving strangely now. It was he. As if a spell – What asinine rot! He’d just let himself be irritated by that stupid, hidebound old bunch of women, those old dragons.

The complexities of caregiving, the sacrifices and rivalries of women, gender inequalities, and emotional labor are all fertile ground for tales of terror. Charlotte Brontë taps into the themes in Jane Eyre. Daphne de Maurier hits the high notes in Rebecca, and Gemma Files explores the often terrifying balancing act of professional ambition and family obligations in Experimental Film. For a case of caregiving gone horribly awry, revisit Misery by Stephen King.

Explore the power dynamics of the workplace.

The sociology chairmanship that Norman covets is but one focal point for the struggles for status at play in Conjure Wife. The chairman’s role represents authority as well as a gateway to influence and opportunity, and Norman isn’t the only person with ambitious eyes on the prize. Evelyn Sawtelle would like to see her own milquetoast husband Hervey in the seat of power.

Leiber skillfully amplifies the stakes by booby-trapping the promotion with elements of supernatural horror. Evelyn and her two wyrd work sisters employ magical tactics to threaten not only Norman’s professional reputation and social standing but his very life.

“You think all those beasts over at Hempnell are just a lot of pussies with their claws clipped?” Tansy asks as she and Norman are hashing out the whole witchcraft question in Chapter Two. “You pass off their spite and jealousies as something trivial, beneath your notice. Well, let me tell you…that there are those at Hempnell who would like to see you dead…”

Norman prides himself on being a rational man, but without Tansy’s protection, his charmed life quickly becomes a nightmare. Losing the chairmanship to Hervey is just a taste of the poison that awaits when he steps outside Tansy’s magic circle. He’s accused of inappropriate behavior, threatened at gunpoint by a student, and suspected of plagiarism in such short order that it forces him to seriously consider the possibility that his wife and the wives of his colleagues are witches engaged in a magical battle for their husbands’ careers.

The workplace is a microcosm of societal power structures, where individuals vie for recognition and influence, often resorting to Machiavellian tactics. Leiber depicts the dark underbelly of ambition, revealing the lengths people are willing to go to secure their positions or to maintain their dominance. Ultimately, by leveraging these power struggles as a source of horror, writers can tap into the deep-seated fears related to our societal and professional aspirations.

Mine the dark depths of horror found in the modern workplace.

Work has been a source of horror throughout history, and the modern workplace continues to provide fertile ground for exploring these themes in literature and art. Whether through the monotonous repetition of tasks, power dynamics between colleagues, or struggles for status and control, writers can craft tales that resonate with readers’ deepest anxieties. By delving into the complexities of the workplace and its impact on individuals’ lives, authors have the opportunity to create gripping stories that shed light on the darker aspects of our professional lives.

Do you have a favorite tale of workplace terror? Share your recommendations in the comments.

My first exposure to Leiber’s Conjure Wife was the 1962 film adaptation Night of the Eagle, which aired in the U.S. as Burn, Witch, Burn.

I feel like you could write your own Occultaria of Albion and look forward to getting my copy of the Conjure Wife to read.

I’d be lying if I said OA hasn’t inspired some future zines of a similar flavor (but stateside of course).

Whenever I work a night shift at the hospital I always think it co you kid be a great setting for a horror story. So many areas , not patient care areas,are creepy at night

Hospitals are already scary, so yes, absolutely. You should write that story…unless you’re worried you’ll scare yourself to death!