“Daphne is the Queen of digging beneath the surface at the ugly, hidden truths that drive and motivate people’s behaviour. She is chief un-masker, the one that peels back the facade that is presented to the world, letting us know that the lives we covet might not be as perfect as we believe. In this way, she delivers insight and a chance for self-reflection. A moment of pause where you look at yourself and think, maybe things are not so bad after all. That she does it so engagingly and weaves gripping plots of all kinds into her stories just makes it all the better. She really can write anything.”

Kelly Shorter | Contrary Reader | @contraryreader

2023 Presiding Judge, Winter Hauntings Ghost Story Contest

Like many middle-aged folks, I’ve accidentally taken up bird-watching as I’ve aged. I’d say it started when we moved aboard our first boat, the Shanti, down in the Gulf of Mexico. My life slowed down, and I spent much more of it outdoors, where birds tend to congregate. Finding myself more frequently in their company, I began to pick up on some of their habits.

For example, I noticed that the shorebirds – the anglers of the avians – tended to keep the same commuter hours as my non-feathered fishermen friends, heading out over Lake Pontchartrain in a great, gliding convoy of pelicans, egrets, and gulls in the wee hours of the morning and heading back inland to roost just about the time their human brethern headed home with their own catch.

Pelican hovering over Lake Pontchartrain as we make our first crossing.

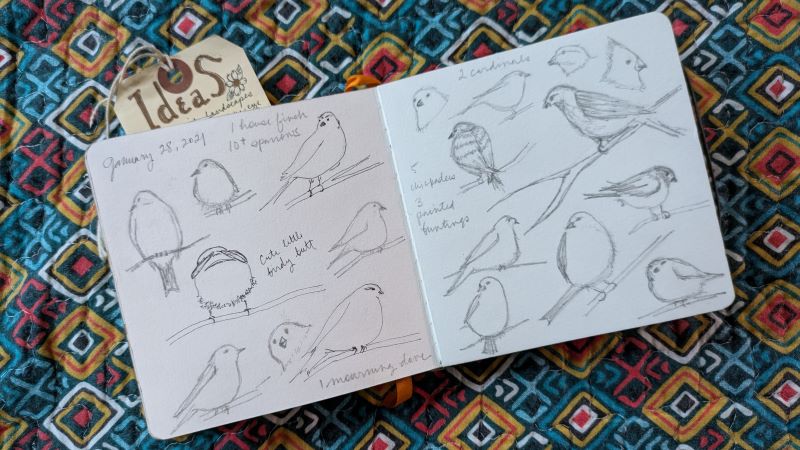

My condolence prize when I moved back on land in the winter of 2020 was a window with a view of two pairs of rare painted buntings. Jack built a feeder and attached it to the sill, and I sat still, silent, and sketching for hours on end in rapt joy as they argued and necked and trilled arias on that tiny wooden stage.

Bird sketches from the winter of painted buntings Down East.

So I could relate to Daphne du Maurier’s protagonist Nat Hocken in her most fowl literary nightmare “The Birds.” Here was a guy who knew his nuthatches from his nightingales. Unfortunately, that doesn’t help much when the birds have gathered en masse to wipe out humanity. You don’t get a pass for being a member of the Audubon Society.

When it comes to weird psychological fiction, few have ever wielded a quill with the deftness of du Maurier. She’s a perennial favorite among those of us who enjoy a good dig in the dirt, as my friend Kelly Shorter, an expert on all things eerie, noted when I asked her what made this maven of the macabre so special. (See her eloquent answer above.)

Among du Maurier’s many spine-tingling tales, few keep readers’ hearts a-flutter as masterfully as “The Birds,” not only because of its chilling storyline but for its brilliant execution in suspense-building. In her tale of nature turning violently against man, she crafts suspense with an enviable subtlety, making it an excellent case study for writers hoping to achieve the same effect in their narratives. Let’s explore three main techniques the Queen uses to grip the reader’s mind and pulse with her cold, clawed talons.

TL;DR: “The Birds” Plot

Protagonist Nat Hocken battles to protect his family amidst a mounting apocalyptic menace, as relentless and inexplicable bird attacks escalate into nationwide terror.

Offer up a worthy sacrifice.

Du Maurier’s first priority in “The Birds” is to paint a sympathetic portrait of our hero Nat, who “because of a wartime disability, had a pension and did not work full time at the farm. He worked three days a week, and they gave him the lighter jobs: hedging, thatching, repairs to the farm buildings.” We learn that lovable Nat’s a family man who enjoys honest labor and takes his lunch outside where he can watch the birds, which he knows by name:

Black and white, jackdaw and gull, mingled in strange partnership, seeking some sort of liberation, never satisfied, never still. Flocks of starlings, rustling like silk, flew to fresh pasture, driven by the same necessity of movement, and the smaller birds, the finches and the larks, scattered from tree to hedge as if compelled.

Nat watched them, and he watched the sea birds too. Down in the bay they waited for the tide. They had more patience. Oystercatchers, redshank, sanderling, and curlew watched by the water’s edge; as the slow sea sucked at the shore and then withdrew, leaving the strip of seaweed bare and the shingle churned, the sea birds raced and ran upon the beaches.

You see how she’s setting you up, don’t you? Nat, decent, vulnerable, knowledgable Nat. Surely, he’s the kind of wholesome, upright character we can expect to overcome a plumed peril of pandemic proportions. Right? Right?!

As the story continues, du Maurier extols gentle Nat’s tempered reactions and his genuine concern for his family, his slow-to-panic attitude and his competence in the face of disaster. Before you know it, you care what happens to him, you fool. When Nat finally accepts the grim reality of the situation and admits his own fears, you’re going to feel that.

As a writer, you want your readers’ reactions to mirror the protagonist’s feelings and responses, so crafting a character the audience cares about is instrumental in luring readers into your trap. Try balancing traits in a way that makes your protagonist relatable, well-rounded, and realistic. Nat knows a lot about birds, but he has questions, too. He’s capable of weathering a little apocalypse, but probably not all of it. He’s brave – and he’s also very, very afraid.

(If you’ve read my past posts, you know I loooooove a worthy sacrifice. One of my other favorites is Sergeant Howie in the 1973 film The Wicker Man. He’s not nearly as likable as Nat, so you won’t mind what happens to him nearly as much. It’ll just feel right. I wrote about his fate here.)

Use cycles to set expectations.

Du Maurier cleverly employs natural cycles, such as the tides and sunrises and sunsets, to cultivate a growing sense of dread and to offer moments of false hope. In the beginning, the attacks seem random and sporadic. However, Nat observes that over time the attacks begin to adhere to a precise timetable, coinciding with the tide’s ebbs and flows.

He got up and went out of the back door and stood in the garden, looking down toward the sea. There had been no sun all day, and now, at barely three o’clock, a kind of darkness had already come, the sky sullen, heavy, colorless like salt. He could hear the vicious sea drumming on the rocks. He walked down the path, halfway to the beach. And then he stopped. He could see the tide had turned. The rock that had shown in midmorning was now covered, but it was not the sea that held his eyes. The gulls had risen. They were circling, hundreds of them, thousands of them, lifting their wings against the wind. It was the gulls that made the darkening of the sky. And they were silent. They made not a sound. They just went on soaring and circling, rising, falling, trying their strength against the wind.

By making the readers anticipate the next attack through these cycles, Du Maurier keeps them perpetually on edge. This cyclic pattern not only builds suspense but also, in a sinister way, provides a false comfort — luring the reader into a predictable rhythm before shattering it with unpredictable events.

As writers, patterns are an invaluable tool in building suspense. Let the readers believe they know what’s coming, only to challenge their expectations.

Leave room for mystery.

Sometimes, what’s left unsaid or unknown is far more terrifying than explicit details. Throughout “The Birds,” there’s an ever-present ambiguity that magnifies the horror. Why are the birds attacking? What’s causing this behavior? These questions remain unanswered because one of the thrills of horror is not knowing. This ambiguity, coupled with Nat’s limited perspective, ensures that the readers remain as uninformed and apprehensive as the protagonist throughout the story.

When the radio goes silent, both Nat and the reader feel cut off from the world and overwhelmed by a creeping sense of isolation and dread. Du Maurier doesn’t share all the information; she doesn’t reveal all of the story’s secrets. She allows the reader to wonder and create their own worst-case scenarios.

They waited. The kitchen clock struck seven. There was no sound. No chimes, no music. They waited until a quarter past, switching to the Light. The result was the same. No news bulletin came through.

Sometimes, the most lethal weapon in your suspense-building arsenal is radio silence. Don’t be afraid to use it. When it comes to writing tales of terror, we can, on occasion, refuse to show or tell to much greater effect.

Fear is a thing with wings. Spread yours.

Du Maurier’s techniques — from the crafting of a relatable protagonist to the manipulation of cycles and the powerful use of ambiguity — provide an infallible guide for creating suspense that soars on the swift wings of killer seagulls. By studying her work and playing with these same principles in your own stories, perhaps you, too, can craft a tale that that sends readers flying into a panic.

Visit the Internet Archive to read Daphne du Maurier’s short story “The Birds” in her 1952 Penguin collection The Birds and Other Stories.

Writing Challenge

Spend an hour or so observing wildlife in your neck of the woods and, then, write a story that involves a trustworthy but vulnerable protagonist, natural cycles, and an unspoken mystery that takes happy-go-lucky animal-lovers on a flight of terrifying fantasy.

Don’t forget!

If you’ve got a Carteret County connection and a head full of ghosts, submit your 1,300-word locally-inspired tale of terror to the EPIC Carteret Winter Hauntings ghost story contest. Learn more.

Those are some nice bird sketches, renaissance woman!

Many thanks, Renaissance friend!