I first fell in love with bull thistle while my husband, son, and I were living aboard our leaky, old sailboat in New Orlean’s Industrial Canal, pre-pandemic. We were tied up at an RV park that happened to have a couple of floating docks. It was not scenic, per se, what with all the gravel and road dust and diesel fumes. Across the canal, a Bunny Bread factory and a Folger’s Coffee factory belched out burnt breakfast fumes intermittently throughout the day. Around us, there were abandoned factories – a place that had manufactured yachts, for instance, and a place that looked like it had been manufacturing nightmares for more than a decade. Burned out cars were as common as twelve-foot alligators; both more common than I find comforting.

Our car crapped out two or three years into our tenure at the not-quite-a-marina, and we were way outside the city proper and its amenities. It was a mile walk to the bus stop along a run-off ditch that was overgrown with switchgrass and cattails and home to watersnakes and little baby snapping turtles that would sun themselves on cast off tires and sofas. There was plenty to see, but in April, I only had eyes for the cutting beauty of the bull thistles, so named because they are as big as bulls and just as likely to tear into your flesh if you tangle with them.

In retrospect, I recognized kinship with the thistle. It’s prickly and obstinate and unapologetically garish with its puffy pink and purple mohawk and its spiked collar. The thistle is a punk among petunias, and as such, it doesn’t require delicate treatment and coddling to thrive. It’ll take over any scrap of dirt left untended and fight you for it. I might just as easily be describing myself on my better days.

Of course, that wild, weedy, ungovernable quality of the thistle is what has made her a fiend in many (though not all) legends. In that way, she’s a reminder that the virtues of a plant (or person or place) largely depend on the perspective of the storyteller. One man’s sore foot is another man’s saved village. You’ll see what I mean. Keep reading.

Botanical Information

Scientific Name: Cirsium vulgare

Folk Names: Common thistle, Spear thistle, Scottish thistle, St. Mary’s thistle, Scotch thistle, Milk thistle

Family: Asteraceae

Habitat and Distribution: Bull Thistle is native to Europe and Asia and has naturalized in North America. It can be found in a variety of habitats, including fields, meadows, pastures, and roadsides. It prefers full sun and well-drained soil.

What makes bull thistle so monstrously beautiful?

In the book of Genesis, God punishes Adam’s disobedience by cursing the earth so that humans would have to toil among thorns and thistles to grow crops for sustenance forever thereafter. Thistles are designed to be a problem, which is pretty monstrous. As American poet Maxine Kumin explains in her poem “Why There Will Always Be Thistles:”

Sheep will not eat it

nor horses nor cattle

unless they are starving.

Unchecked, it will sprawl over

pasture and meadow

choking the sweet grass

defeating the clover

until you are driven

to take arms against it

but if unthinking

you grasp it barehanded

you will need tweezers

to pick out the stickers.

In a popular Islamic tale, the Prophet Muhammad orders a thistle to be uprooted and thrown away, calling it a plant of the cursed devil. In her poem, Kumin expresses the futility of any effort to uproot thistle from her infernal terrain:

Outlawed in most Northern

states of the Union

still it jumps borders.

Its taproot runs deeper

than underground rivers

and once it’s been severed

by breadknife or shovel

-two popular methods

employed by the desperate-

the bits that remain will

spring up like dragons’ teeth

a field full of soldiers

their spines at the ready.

The truth is that the relative mischief and mayhem of wild thistle depends on your relationship with her. Even within one culture, she’s super-abundant in symbolic potential, representing both hardship and resilience, pain and protection.

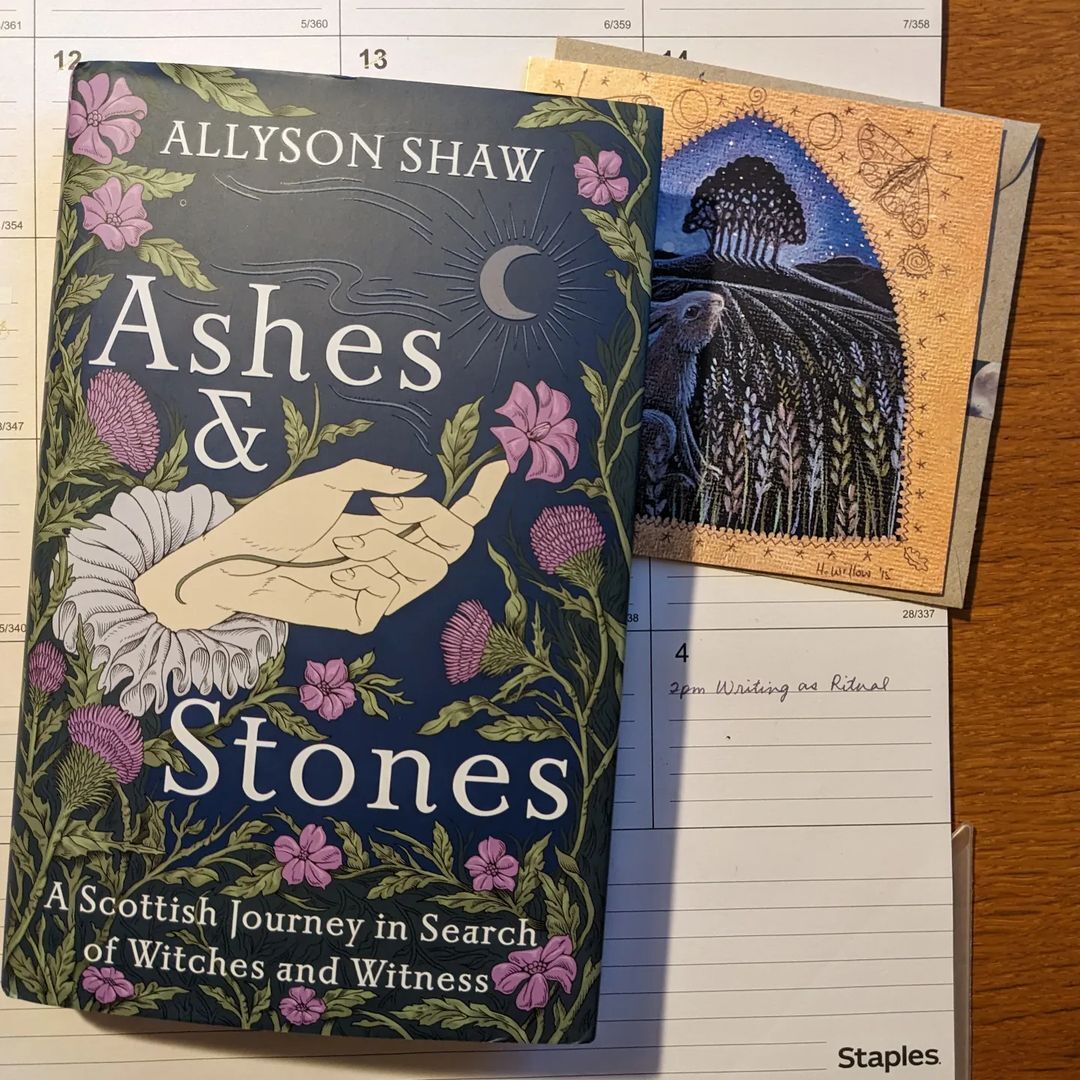

Thistle makes several appearances in Allyson Shaw’s moving recent release Ashes & Stones: A Scottish Journey in Search of Witches and Witness. In the most striking, Allyson describes Isobel Gowdie’s confession under torture. Isobel tells her judges that she yoked a plow to a team of frogs and led them widdershins around a field so that “thistles and briars might grow there,” effectively destroying her enemy’s food supply Old Testament-style. It’s fascinating to me that this accused witch, herself a weed in the garden of proper gentlefolk, employed the Genesis creation myth in her own personal myth-making. In Isobel’s confession, she casts herself as the omnipotent hand of justice, capable of enacting the same punishment on her enemies as Yahweh in his wrath.

Despite its biblical origin story, Isobel’s use of the thistle was deemed diabolical by the Scottish judicial system of the time. However, another Scottish legend credits thistle’s spikes with national heroism. According to lore, an invading Viking stealthily approaching a Scottish village stepped on a thistle and cried out in pain. In so doing, he revealed his position, and the alerted villagers were able to thwart the invaders. While no one wants to tangle with thistle’s prickles, she does offer a natural line of defense to those who live within her enchanted territory. Suddenly, thistle isn’t looking so shabby.

It’s complicated.

For many people, thistle is a noxious weeds with teeth and talons who invades otherwise respectable landscapes. Her taproots run deep, making it nearly impossible to eradicate her, but those same deep tap roots are part of thistle’s magic. She favors disturbed and damaged landscapes, and her taproot can grow several feet deep into compacted ground. Down in the depths, she can access water and nutrients that other plants can’t reach, and when she dies, she brings them all back up to the surface, enriching soil and creating channels for air and water. In this way, her resilient persistence clears the path for more delicate flowers and a more diverse, healthier ecosystem.

She’s also proved benevolent to humans who are willing to look past her prickly defenses. In fact, medical research suggests that folk medicine treatments using thistle can promote good health and serve as a primary defense mechanism against diseases. Perhaps more importantly, humans aren’t the only creatures Mother Nature is providing for when she does her gardening. Thistles are a favorite snack of both goldfinches and red-winged blackbirds and provide a cozy home for a butterfly’s chrysalis, which is good enough for me.

References

- The Arabian Nights: A Companion by Robert Irwin

- The Language of Flowers: Symbols and Myths by Marina Heilmeyer

- Ashes & Stones: A Scottish Journey in Search of Witches and Witness by Allyson Shaw

Writing Challenge

Write a scene, story, or poem that explores the concept of monstrous beauty inspired by the bull thistle. Incorporate the prickly and formidable nature of the plant, along with its strikingly beautiful flowers, as a metaphor for the harsh realities of life and its unexpected moments of beauty. Use descriptive language and sensory details to evoke the thistle’s menacing yet alluring presence, and consider the ways in which the thistle can serve as a symbol for resilience, survival, and the triumph of nature over adversity.

Leave A Comment