Ghosts have haunted the pages of literature since the first known tale was inscribed in clay tablets more than four thousand years ago. In the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, the legendary king sends his BFF Enkidu to the underworld to retrieve several lost items. We don’t know what the lost items were because, ironically, that section of the tablet was lost. What we do know is that Irkalla, the queen of the House of Darkness, decides to keep Enkidu in the land of the dead. Not being entirely heartless (or maybe because she is entirely heartless), she allows his spirit to pass through a crack in the earth to tell his friend Gilgamesh of his fate and of the fate of all mortals, kings and peasants alike, who travel:

to the house where those who enter do not come out,

along the road of no return,

to the house where those who dwell, do without light,

where dirt is their drink, their food is of clay,

where, like a bird, they wear garments of feathers,

and light cannot be seen, they dwell in the dark,

and upon the door and bolt, there lies dust…everywhere I looked there were royal crowns gathered in heaps,

everywhere I listened, it was the bearers of crowns,

who, in the past, had ruled the land,

but who now served Anu and Enlil cooked meats,

served confections, and poured cool water from waterskins.

A Matter of Grave Concern

Despite his goddess mother, it seems that Gilgamesh is subject to the same fate as his mortal subjects, and so this macabre message from the Netherworld terrifies him. In fact, it is this vision that compels him to go on his famous quest in search of everlasting life. Spoiler: turns out there’s no such thing.

It stands to reason that this wasn’t the first ghost story. Rather, it’s the oldest surviving ghost story. However, we can already see the kernels of ghostly tropes that remain in tales of terror today, most notably, the ghost as a warning to an arrogant protagonist who will ultimately be transformed by the specter’s message. Think: Ebenezer Scrooge, haunted by the chain-jangling Marley, who warns Scrooge of the fate of those weighed down by the burdens of their past greed and misdeeds.

Illustration by Fred Barnard (1846-1896) of Jacob Marley and Ebenezer Scrooge in ‘A Christmas Carol’ (1878). https://picryl.com/media/jacob-marley-fred-barnard-1878-cf820c

The Chain Gang

Old Marley’s metal attire may give modern, Sid Vicious and the Sex Pistols vibes, but gaunt, haggard men wearing padlocks and chains was an established ghost trope well before the time A Christmas Carol was published in 1843. In one of his 247 surviving letters to philosophers, historians, emperors, et al., Roman writer Pliny the Younger tales the story of the philosopher Athenodorus, who rented “a large and spacious, but ill‑reputed and pestilential house, [wherein] In the dead of the night a noise, resembling the clashing of iron, was frequently heard, which, if you listened more attentively, sounded like the rattling of fetters; at first it seemed at a distance, but approached nearer by degrees; immediately afterward a phantom appeared in the form of an old man, extremely meagre and squalid, with a long beard and bristling hair, rattling the gyves on his feet and hands.”

This apparition was so unsettling that all who attempted to live in the house ultimately died of fright until, at last, it was abandoned entirely. That is, until Athenodorus comes along. He isn’t in the least afraid of the ghost – even upon hearing of the terrifying end of all the past tenants.

On his first night in the home, while writing late into the evening, he hears the rattling chains of the ghost. However, Athenodorus remains unrattled, calmly ignoring the noise until the spirit enters his room. Even then, he makes the ghost wait until he has come to the end of his studies before he attends to its beckoning. When he does finally follow the ghost, it leads him to the discovery of a chained skeleton, which when properly buried brings an end to the haunting and a beginning to a whole new ghost story trope.

The Cold Case

Athenodorus’ ghost wasn’t the last or the most famous spirit to seek revenge for their unjust murder or improper burial. It was Shakespeare’s Hamlet that proved the dramatic power of this particular trope. Written in 1601, Hamlet uses a conversation with the restless spirit of the protagonist’s father as the inciting incident in one of his most haunting plays:

GHOST

I am thy father’s spirit,

Doomed for a certain term to walk the night

And for the day confined to fast in fires

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away. But that I am forbid

To tell the secrets of my prison house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their

spheres,

Thy knotted and combinèd locks to part,

And each particular hair to stand an end,

Like quills upon the fearful porpentine.

But this eternal blazon must not be

To ears of flesh and blood. List, list, O list!

If thou didst ever thy dear father love—

HAMLET

O God!

GHOST

Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder.

You know what happens after Hamlet’s haunting visitation. Death. Lots of death. Like, seriously, everybody dies, making Hamlet an early progenitor of Friday the 13th, I Know What You Did Last Summer, and all the slasher films to follow in some ways, methinks.

But at least the ghost of Hamlet’s father can rest in peace knowing his cold case has been solved and justice has been served. And then some.

Home is Where the Heart is (Buried)

The story of Athenodorus was one of the earliest haunted house tales, but the trope picked up steam in the early 19th century during the Gothic and Romantic literary movements. Gothic tales, in particular, like Edgar Allan Poe’s well-known “The Fall of the House of Usher” and “The Old Nurse’s Story” written by Elizabeth Gaskell, often featured remote and decaying mansions where eerie occurrences involving tragic family secrets threatened the bedeviled residents or their hapless visitors. In general, you can expect home-bound haints to be tied to violent murders, bitter betrayals, or unresolved conflicts that continue to influence the present. Frequently, the house itself becomes a malevolent character, playing on our fear of the familiar turning hostile and the past haunting the present.

The haunted house story remains one of the most popular ghostly tropes and has been packed up and moved into the modern era by some of my personal favorite 20th and 21st century authors, such as Shirley Jackson, who wrote The House on Haunted Hill in 1959, and the contemporary YA author Jonathan Stroud, whose imaginative Lockwood & Company series tramples all the ghost story tropes. Interestingly, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” The House on Haunted Hill, and Lockwood & Company have been made into Netflix original series, proving the staying power of the haunted house story. But then again, this particular trope even has a ride at Disney World, so that was never really in question.

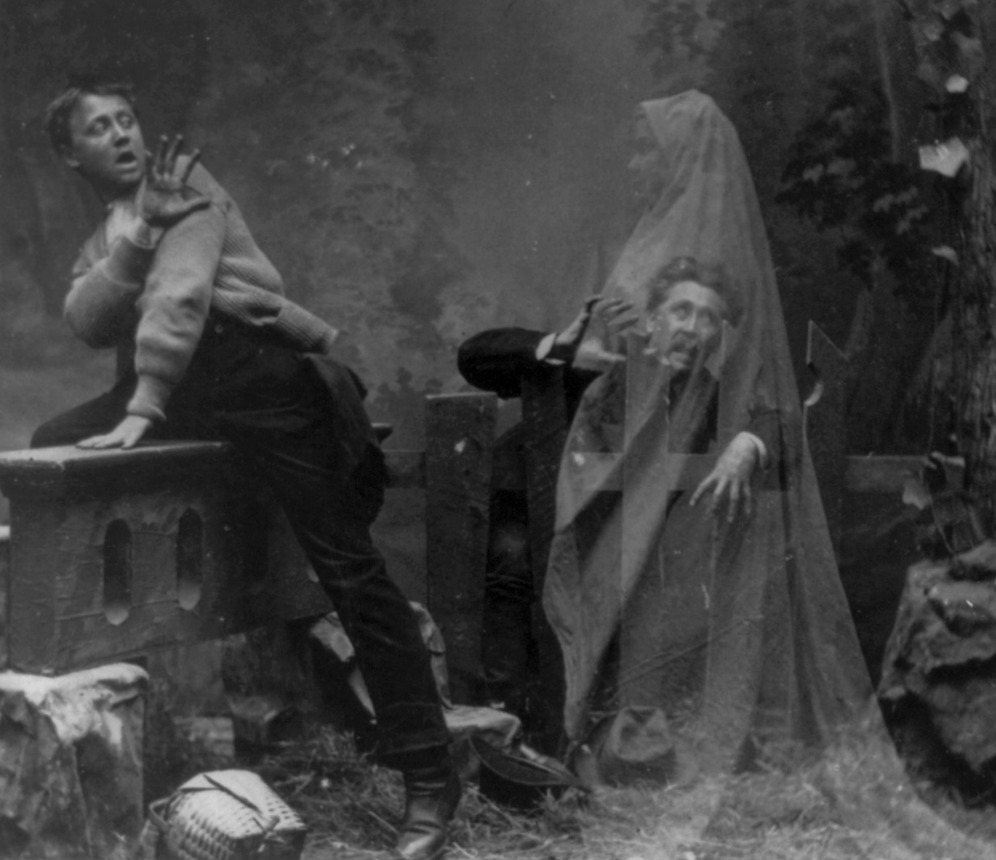

Em-bedded in Popular Culture

One of the most iconic ghost tropes — the image of the linen-draped specter — can be traced to the Victorian theater. In centuries past, before coffins became widespread, bodies were often wrapped in shrouds before burial, and these grim linens were often associated with the restless dead. In addition to being a convenient mode of transporting corpses (the poor could easily be rolled up in the sheets from their death bed for a makeshift coffin), bedding became a convenient way to depict the dead in art. White sheets made a quick costume change for actors masquerading as ghosts and created a visual shorthand that audiences soon came to recognize.

The Victorians may have invented the sheet ghost, but the Edwardian author M.R. James, arguably the most prolific and beloved ghost story writer of all times, took the haunted linen tradition to another level. I’ve written about James on The Other Blog before, in particular regarding his unique genius in using bedding to create dread in his short story “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,” so I won’t belabor the point here. I also cannot bring myself to share the most compelling passage because I wouldn’t spoil the experience for you. You need to read the whole story (preferably in bed and under the covers). However, here’s a teaser:

There had been a movement, he was sure, in the empty bed on the opposite side of the room. To-morrow he would have it moved, for there must be rats or something playing about in it. It was quiet now. No! the commotion began again. There was a rustling and shaking: surely more than any rat could cause.

I can figure to myself something of the Professor’s bewilderment and horror, for I have in a dream thirty years back seen the same thing happen; but the reader will hardly, perhaps, imagine how dreadful it was to him to see a figure suddenly sit up in what he had known was an empty bed.

By the 20th century, children’s cartoons like Caspar the Friendly Ghost and It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown as well as comedies like Ghostbusters cemented this visual, and ghosts in sheets became a fun, non-threatening way to represent the supernatural. In Halloween traditions, it became a simple DIY costume for kids, further embedding it in popular culture. Today, the “sheet ghost” trope is mostly used for humorous or nostalgic purposes, though it occasionally appears in horror films as a subversive or eerie image, such as in the movie A Ghost Story, where the ghost is depicted as a figure in a sheet for a more poignant, emotional effect.

Now, you try.

Above, I’ve given you a catalog of classic ghost stories to review with links where you can find most of them for free online. Below, you’ll find prompts that encourage you to play with these tropes. If you’ve been haunted by writer’s block with the ghost story contest deadline looming, now’s the time to settle down like Athenodorus and get focused. Come back and tell me which trope you chose to make your own!

Write a story where a child dressed as a sheet ghost for Halloween starts seeing real sheet-covered spirits that no one else can see.

Leave A Comment